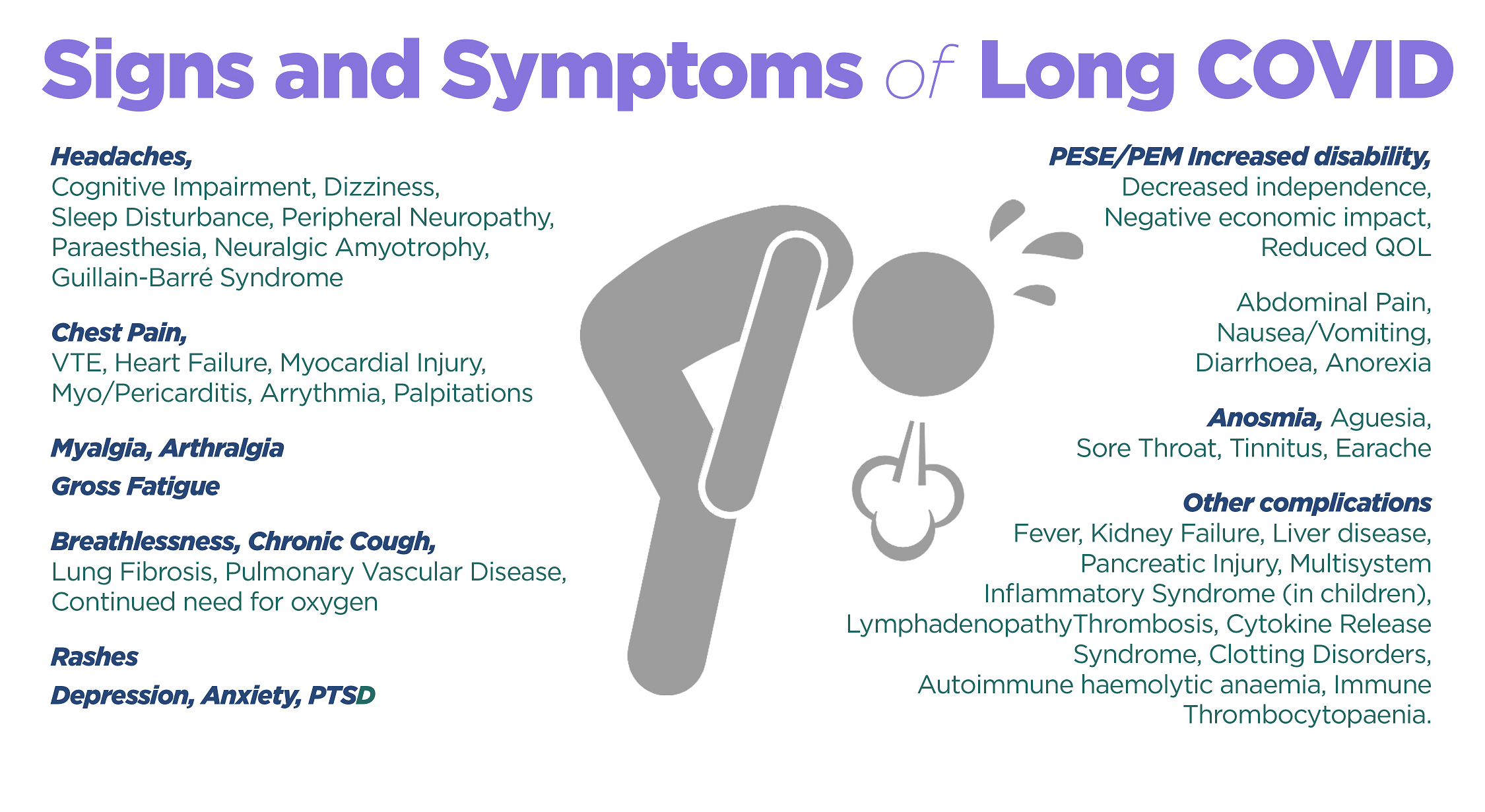

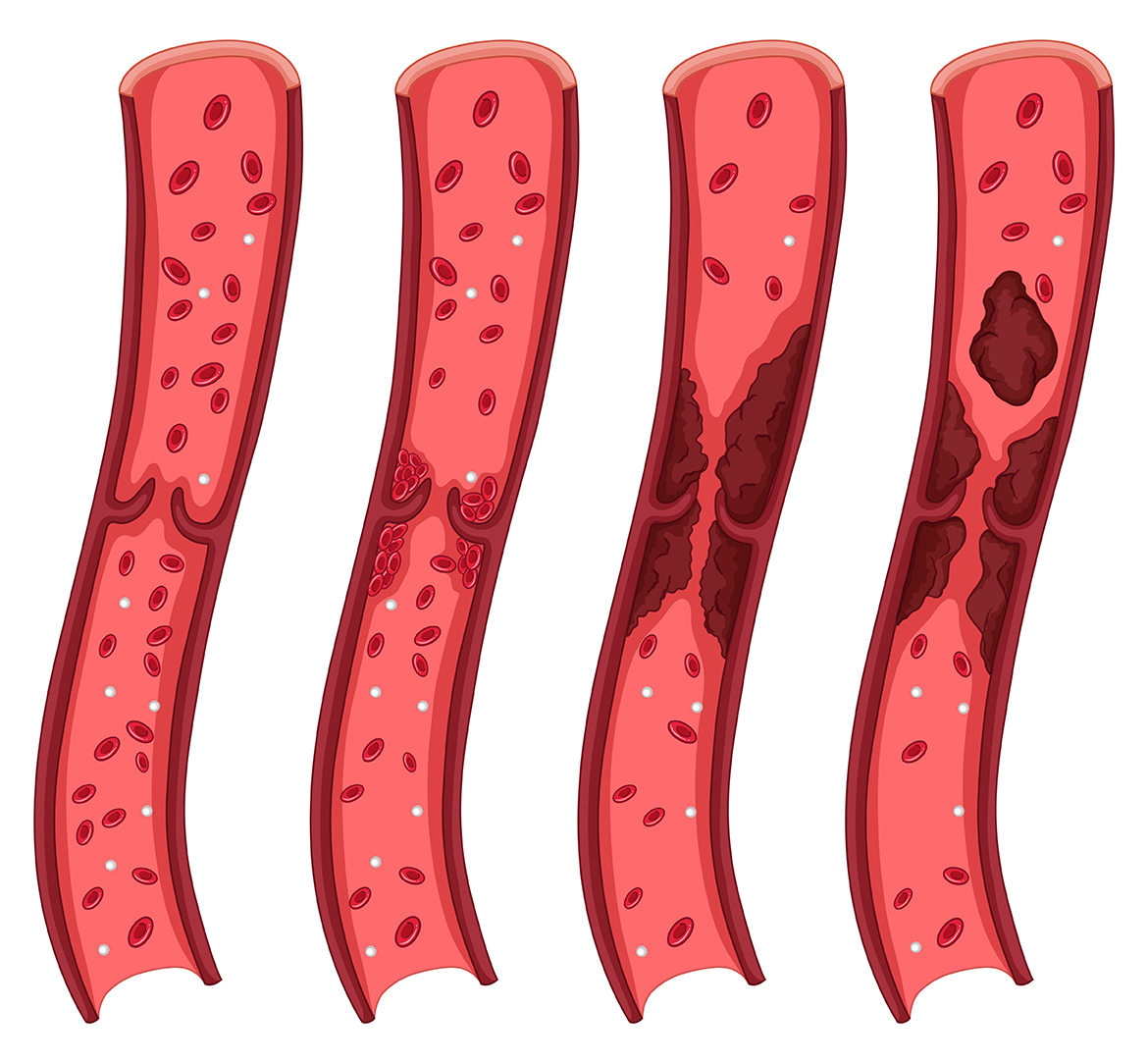

Post-acute COVID-19 infection reported pulmonary, hematologic, cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, renal, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and dermatologic effects.

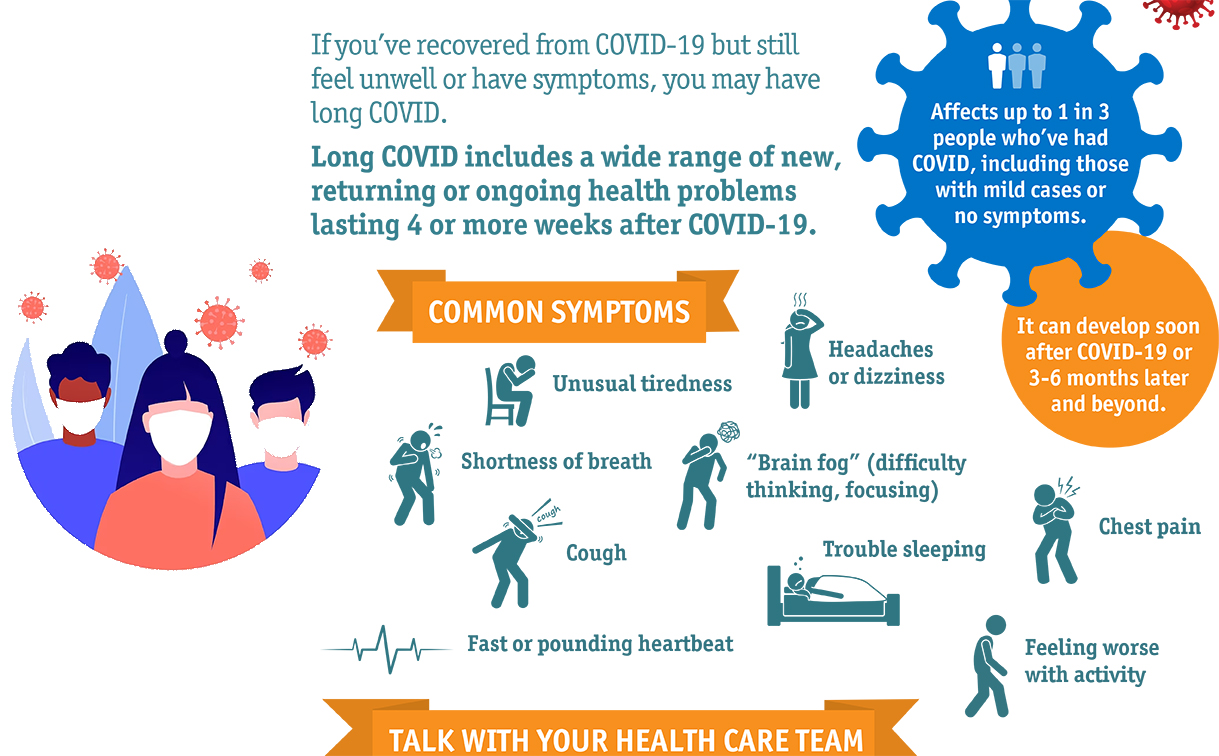

A wide range of other new or ongoing symptoms and clinical findings can occur in people with varying degrees of illness from acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, including patients who have had mild or asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. These effects can overlap with multiorgan complications, or with effects of treatment or hospitalization. This category is heterogeneous, as it can include patients who have clinically important but poorly understood symptoms (e.g., difficulty thinking or concentrating, post-exertional malaise) that can be persistent or intermittent after initial acute infection with SARS-CoV-2. Commonly reported symptoms include:

- Dyspnea or increased respiratory effort

- Fatigue

- Post-exertional malaise* and/or poor endurance

- Cognitive impairment or “brain fog”

- Cough

- Chest pain

- Headache

- Palpitations and tachycardia

- Arthralgia

- Myalgia

- Paresthesia

- Abdominal pain

- Diarrhea

- Insomnia and other sleep difficulties

- Fever

- Lightheadedness

- Impaired daily function and mobility

- Pain

- Rash (e.g., urticaria)

- Mood changes

- Anosmia or dysgeusia

- Menstrual cycle irregularities

- Erectile dysfunction

Reference : https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/post-covid-conditions.html